By Farea Al-Muslimi and Adam Baron

Executive summary

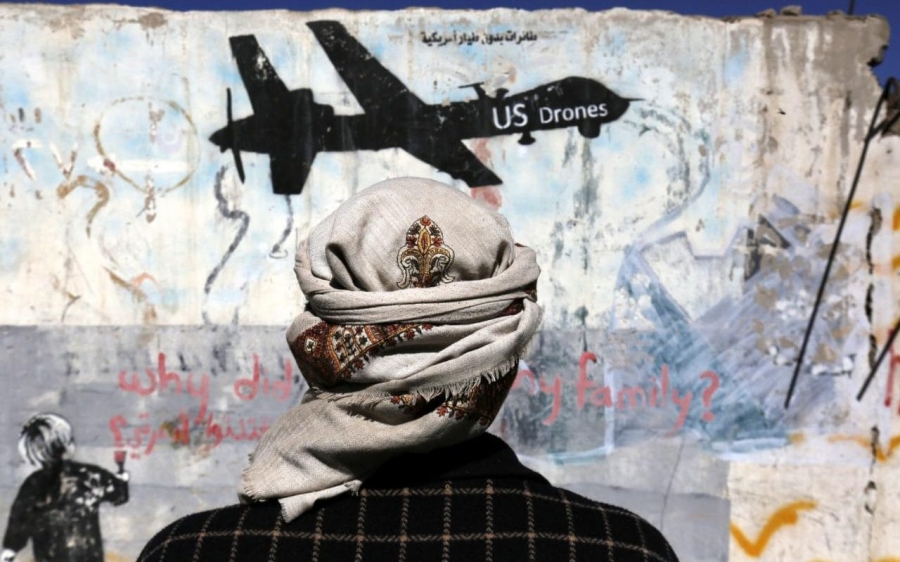

Similar to US counterterrorism efforts in Yemen under President Barack Obama, the newly minted White House administration of Donald Trump has shown little appetite to explore non-military policy options to supplement the use of American firepower in Yemen. Indeed, shortly after taking office President Trump authorized the escalation of drone strikes and special forces operations in Yemen. The Trump administration’s 2017 budget proposal to congress also outlines massive cuts in US diplomatic and humanitarian spending, even as the UN declared last month that Yemen faces the largest food security emergency in the world. Such a myopic focus on the military option in the battle against Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) indicates a failure to grasp why AQAP has expanded so successfully in Yemen despite well more than a decade of US counterterrorism efforts in the country.

Among AQAP’s core strengths is its membership’s understanding of the historical context and socio-political, tribal, security and economic dynamics at play in the areas in which the group embeds itself; this allows the group to tailor its tactics and leverage local circumstances to expand its support base, operational capacity, and absorb losses. Since the onset of civil war in Yemen, AQAP has exploited the country’s sectarian polarization, the collapse of the state and security institutions, and the catastrophic humanitarian crisis such that today AQAP is a more potent force than ever before.

In crafting its counterterrorism policies for Yemen, it is incumbent upon the new US administration to realize that the use of military force alone will almost certainly fail to defeat AQAP, and will indeed likely be counterproductive to that end given the civilian casualties heavy-handed military interventions inevitably entail and how AQAP is able to exploit these in its recruitment and propaganda efforts. To be successful, the battle against AQAP must be multifaceted, and include the promotion of efficient local governance, improved access to basic services, more equitable judicial mechanisms and the establishment of effective local security forces. Most importantly, counterterrorism efforts in Yemen cannot be approached in isolation to the country’s ongoing civil war and catastrophic humanitarian crisis – as long as such an environment persists AQAP will continue to thrive.

The following paper is thus an examination of the rise of AQAP in Yemen, and in particular how it has adapted and embedded itself within the social fabric of the three Yemeni governorates that have been most frequently targeted by American counterterrorism efforts – Al Bayda, Abyan and Shabwa.

A brief history of AQAP

Yemen is the ancestral home Osama Bin Laden and the country has long been a feature of the Al Qaeda founder’s designs for the global jihad. Mujahadeen fighters returning to Yemen from Afghanistan, following the war against the Russians in the 1980s, played a key role in defeating southern forces in Yemen’s 1994 Civil War.[1] Many of these fighter were then responsible for forming a succession of extremist Islamic groups responsible for carrying out attacks against both domestic and western targets in Yemen, with the most prominent of these being the bombing of the USS Cole in the port of Aden in the year 2000, which killed 17 American sailors and injured 39.

It was not until 2009, however, that these jihadi groups attained effective operational and structural coherence, when the Yemeni and Saudi Arabian branches of Al Qaeda integrated and publically announced the emergence of the new entity, Tanzim al-Qaeda fi Jazirat al-Arab, or Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The leader of the new joint-venture was Nasir al-Wuhayshi, a former personal secretary to Bin Laden who had escaped Yemeni prison in 2006, and his deputy, Said al-Shihri, a Saudi who was captured in Afghanistan in 2001 and transferred to the US Guantanamo Bay detention facility in Cuba; he was repatriated to Saudi Arabia in 2007 where, after being released from a rehabilitation program, he traveled to Yemen and rejoined Al Qaeda[2].

AQAP soon began launching attacks under its new moniker, expanding its ability to hit both foreign and domestic targets inside Yemen and abroad. Incidents attributed to AQAP outside Yemen have included the Christmas 2009 failed attempt by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab to blow up a Northwest Airlines Flight as it was landing in Detroit, and the January 2015 attack by gunmen on the offices of Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris, which left 12 dead and 11 wounded. AQAP has also gained prominence through its use of English language media: the extremist Yemeni-American preacher Anwar al-Awlaki regularly posted video sermons online in fluent English, promoting attacks on civilian targets in Western countries, while also helping to establish Inspire, AQAP’s semi-regular English-language online magazine, in 2010[3].

In recent years AQAP has heavily exploited the increasing polarization of Yemeni society, the retreating authority of the Yemeni state and security services, and gained significant financial largess when it controlled the port city of Mukalla from April 2015 to April 2016, such that today AQAP and its affiliate Ansar al-Sharia are arguably stronger and wealthier than they have ever been[4]. AQAP and Ansar al-Sharia currently have an active presence in no less than 11 Yemeni governorates, continually launch attacks on Yemeni-government allied troops, the rebel Houthi movement and its allies, as well as ideologically opposed tribal leaders. AQAP also regularly boasts on its media outlets that the group is continuing to plan attacks in Western countries.

Continuity of US counterterrorism policy in Yemen

American drone strikes and other Western-back counter-terrorism measures in Yemen began under US President George W. Bush, with the Obama administration dramatically ramping up the frequency of drone strikes[5]. Both Awlaki and Inspire’s editor-in-chief, American citizen Samir Khan, were killed in a US drone strike in Yemen’s Al Jawf governorate on September 2011, while Shihri and Wuhayshi were killed in strikes in 2013 and 2015, respectively. AQAP has, however, shown operational resilience and has continually regrouped and rebounded from these losses.

Under the Obama administration, among the primary targets of US military operations against AQAP in Yemen were the governorates of Abyan, Al-Bayda and Shabwa; under President Trump these governorates have remained primary targets. Indeed the first counterterrorism activities of Trump’s tenure began the Friday he took office and continued through that weekend in a series of missile strikes against suspected AQAP targets in the governorate of Al-Bayda[6].

Shortly after entering the White House President Trump then authorized a Pentagon request to have areas of Yemen deemed zones of “active hostilities”. In May 2013 the Obama administration had limited the military’s use of force to operations in which there was “near certainty” that no civilians would be killed; the Pentagon request Trump approved lowers that bar to allow for civilian casualties “as long as they are deemed necessary and proportionate to a legitimate military objective”, as reported by the New York Times[7]. On the morning of January 29, US Special Forces backed by Emirati troops then carried out a raid in the village of Yakla, Al-Bayda governorate, killing 14 AQAP affiliates – two of whom were members of a powerful local tribal family – and 25 civilians, including nine children under the age of 13[8]. Drone strikes and other US operations have continue since, with the most sustained barrage coming between March 2 and March 6, when an unprecedented surge saw an estimated 40 American airstrikes in the governorates of al-Bayda, Shabwa and Abyan[9].

Similar to US efforts under Obama, however, thus far under Trump there has been little American exploration of counterterrorism policy options to supplement the direct use of force. Simultaneously, the president’s recent budget proposal to congress lays out billions of dollars in cuts to US foreign aid spending and diplomatic efforts[10]. This, while the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization announced in February that Yemen faces the world’s largest food security emergency; 10.3 million people are considered to be in need of immediate humanitarian assistance in order to “save and sustain their lives” with some 3.3 million people, including 2.1 million children, being “acutely malnourished”, or in other words, starving[11].

Given the scale of the catastrophe in Yemen, the Trump administration’s singular focus on the military option is myopic and ignores the factors that have enabled AQAP’s continued expansion in the country. AQAP cadres have deep operational awareness of the historical context and socio-political, tribal, security and economic dynamics present in the areas in which they embed themselves. This has allowed the group to repeatedly tailor its operations to the specific circumstances it encounters, adapt, leverage local realities, the civil war and the humanitarian crisis to strengthen its support base, increase its operational capacity, and recover from tactical losses.

Any counterterrorism strategy that seeks to dislodge and defeat AQAP in Yemen that does not take in account the inherent complexities at play on the ground – and in particular in the areas where AQAP has solidified its presence – will almost certainly fail. The following is thus an overview of the specific socio-political, tribal, security and economic dynamics of the three Yemeni governorates – Al-Bayda, Abyan and Shabwa – that have featured most prominently in American counterterrorism operations in the country to date.

Three centers of AQAP activity:

Al-Bayda

Al-Bayda governorate sits at the strategic center of Yemen, being the midpoint between the country’s historic north-south divide, sharing borders with eight other governorates as well as being the meeting point between various tribal areas. As such the province has featured frequently in Yemeni conflicts, both in the civil war of the 1960s and the ill-fated leftist insurgencies of the 1970s. While a number of Al-Bayda natives gained prominence as part of the “global jihad” – most notably Nasser al-Wuhayshi, who hailed from the southern district of Mukayras – AQAP and its predecessor groups’ activities were minimal here until the last five years.

This began to change after the death of Ali Ahmed al-Thahab, head of the powerful al-Thahab family from the Qaifah tribe, based in the Qaifah region in Al-Bayda’s northwest. Following his death in late 2010 there was disagreement within the family about who would succeed him as patriarch, leading a vicious and bloody conflict amongst the extended family.[12] Sheikh Tareq al-Thahab, the heir apparent, and his brothers Qaid and Nabil then sought out allegiance to AQAP to gain leverage over their opponents. While the brothers were related by marriage to Anwar al-Awlaki, and Qaid had previously been arrested for attempting to go to Iraq to fight against American forces there, the entwining of the al-Thahab family with AQAP was very much motivated by political and tactical expediency rather than to satisfy deep-seated ideological convictions.

In January 2012 AQAP-affiliated fighters – under the leadership of Sheikh Tareq al-Thahab – then seized control of the town of Rada, in the governorate’s northwest[13]. While tribal mediation later the same month secured the withdrawal of AQAP fighters from Rada – and shortly after Tareq himself was killed – the militant group’s presence in Al-Bayda, and particularly the area surrounding Qaifah, continued to grow[14]. This was in large part facilitated by the security vacuum left by the withdrawal of the Yemeni army when it split into factions following the country’s 2011 “Arab Spring” uprising – an event that led to the deterioration of the security situation and a boon to AQAP in many areas of Yemen. Military offensives by elements of the Yemeni army in the southern governorate of Abyan, particularly in the Spring of 2012, also drove many AQAP fighters to withdraw north into Al-Bayda governorate and the areas around Qaifah.

Nowhere else in Yemen has AQAP been able to embed itself as deeply in the tribal fabric of society than in al-Bayda, and through continuing to expand and leverage its ties to key members of the al-Thahab family AQAP has been able create the narrative that it is a protective force for locals; a framing that has gained increasing acceptance even amongst those with little ideological sympathy with the group. Yemeni government attempts to reassert military control over the area – notably, a major offensive in January 2013 – and continued US drone strikes have resulted in a continuous stream of civilian casualties, fueling public anger and bolstering AQAP’s recruitment efforts as locals who have lost loved ones seek out the group as a means attain justice and vengeance[15].

Soon after the Houthi rebels and the allied forces of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh overtook the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, in September 2014, they invaded Al-Bayda governorate and seized control of Rada and large parts of the Qaifah region. Though some locals welcomed the purging of AQAP, others saw the Houthi advance as a general assault against the people of Al-Bayda and took up arms against the Houthis, often fighting alongside AQAP if not directly joining the group or its affiliate Ansar al-Sharia. As the sectarian tone of the Yemeni conflict has deepened, some have increasingly come to view AQAP as the lesser of two evils relative to the Houthis.[16] This framing was implicit in AQAP’s public statement following the US Special Forces raid on Yakla in January this year and subsequent drone strikes; AQAP claimed that the American military operations were aiding Houthi-allied forces, and that it would be a Houthi victory if AQAP were forced from Qaifah as Marib and Shabwa would then fall to the Houthis as well; AQAP then urged Yemenis to join the group to prevent this from happening.

It is important to note that amongst key social, tribal, religious and militia figures in Al-Bayda, membership or affiliation with AQAP is typically amorphous and measured by degrees and circumstances, rather than official status. This has been apparent in how those killed in recent US military actions have been variously identified: for example, Abdulraouf al-Thahab, among the targets of the January 29 raid, was cast by some elements of the internationally recognized Yemeni government as an important tribal ally against the Houthis, despite al-Thahab’s longstanding ties to AQAP[17]. Similarly, President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi – head of the internationally recognized government of Yemen – appointed Nayif Salih Salim al-Qaysi governor of Al-Bayda in December 2015; in May 2016 the US Department of the Treasury then declare al-Qaysi a “Specially Designated Global Terrorists”, calling him a “senior AQAP official and a financial supporter of AQAP”.[18] Al-Qaysi remains governor of Al-Bayda as of this writing.

Abyan

Abyan had been know as a bastion of radical leftism before is was one for radical Islam, with many from the governorate having had leading roles in the socialist and Marxist forces that fought the United Kingdom-allied sheikhdoms and sultanates of South Yemen in the 1960s, eventually leading to the creation of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY). Abyan initially saw many of its native sons rise to prominence within the PDRY administration, most notably, PDRY head of state Ali Nasser Mohamed. This changed following the decisive defeat of Ali Nasser’s forces during 1986 civil war in South Yemen, following which he and thousands of members of Abyan’s officialdom fled to North Yemen, leaving Abyan to suffer a dramatic decline in living standards and marginalization under the new regime.

North and South Yemen unified in 1990, following which Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh in the north set out to dominate the south through sowing political divisions, in particular through cultivating relationships with the elite among the Abyani exiles and leveraging their grievances against the other southern political parties. Most notable amongst these exiles was Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, whom Saleh eventually named vice president.[19] In parallel, elements of the Saleh regime also aimed to capitalize on the mujahadeen fighters returning from Afghanistan, facilitating their resettlement in the south to help erode the influence of the Yemeni Socialist Party.[20]

Among the returnees was Sheikh Tareq al-Fadhli, a scion of a highly-regarded Abyani family who had fought with Osama Bin Laden in Afghanistan, and who once back in Yemen used his network of connections to facilitate the relocation of other fighters from Afghanistan – both Yemeni and non-Yemeni – to the country.[21] These fighters coalesced into the Aden-Abyan Islamic army and carried out a slew of assassinations against Socialist Party officials, and later allied with Saleh and the other northern forces in Yemen’s 1994 North-South Civil War.

Over time many Afghan returnees settled back into civilian life; others, however, maintained focus on militant jihad and eventually began targeted attacks on the Yemeni government and security forces, as well as a number of operations against western targets, including tourists in Yemen and the USS Cole bombing. The Aden-Abyan Islamic Army was eventually subsumed into AQAP, and Abyan continued to be a center of the group’s operations.

As state control over much of the country began to recede in 2011, Ansar al-Sharia took advantage by seizing control of the cities of Zinjibar and Jaar and – despite remaining under a degree of pressure from both Yemeni government forces and American airstrikes – effectively succeeded in carving out Islamic statelets. The group established its own governance structures, imposed its strict interpretation of Islamic law, and began to providing public services that – owing to the central government’s previous neglect – were generally of higher quality than what residents had been receiving. AQAP and Ansar al-Sharia’s propaganda arms frequently promoted these governance efforts, with even locals ideologically opposed to AQAP speaking favourably of the militants’ focus on winning hearts and minds, even if the flood of internally displaced people out of Abyan attested to a more mixed reality.[22]

By the middle of 2012, a US-backed Yemeni government military offensive incorporating anti-Al Qaeda “Popular Committees”, made up largely of local tribesmen, forced Ansar al-Sharia to retreat from Zinjibar and Jaar, with the largest portion of the jihadist fighters redeploying to mountainous areas to the east of the city. Importantly, however, numerous members of the group simply reintegrated themselves into civilian life.

Despite initial government rhetoric regarding large-scale development and rebuilding, little was forthcoming following the recapture of the towns and the displacement of AQAP, while promises to Popular Committee fighters regarding financial support and incorporation into the army were overwhelmingly unmet, even as their leadership continued to be the target of extremist attacks. The subsequent weak security environment allowed AQAP and its allies to maintain their foothold and influence, with anecdotal evidence suggesting that various Popular Committee fighters began to “freelance” for AQAP in order to secure an income.[23]

The Houthi and allied forces’ 2015 advance south from Sana’a into Abyan, and subsequent attack on Aden city, significantly altered local dynamics. President Hadi called upon the Popular Committees to defend the city, which exacerbated the security vacuum around much of the rest of the governorate as these fighters left their posts for Aden. As the city then descended into brutal street combat, the Houthis and allied forces replaced AQAP as the primary threat and immediate adversary in the minds of locals. Indeed, AQAP militants were often fighting alongside pro-Hadi and mainstream anti-Houthi forces, who just as often would turn a blind eye to the jihadists’ participation in the battle.[24]

After the Houthis were dislodged from Aden, Ansar al-Sharia and AQAP were able to retake Zinjibar and Jaar under the guise of liberating the towns from the Houthis; members of the Abyan Popular Committees have alleged that President Hadi and his allies effectively gave up portions of the governorate to AQAP without a fight. The jihadist forces held the towns until May 2016, when mediation through local tribes led to an agreement whereby AQAP withdrew its fighters from Jaar and Zinjibar, though the group has since re-established a discrete but substantial presence in the towns.[25]

As the frontlines have moved farther north out of Abyan and the immediate Houthi threat has diminished, local authorities and notables in the governorate – often with foreign prompting – have begun shifting their attention back to combating AQAP and Ansar al-Sharia. The Emirati government, for instance, has trained numerous security entities and dispatched them across Abyan to combat militant extremists, though AQAP has continued to managed to sustain its presence and launch counter attacks against the Emirati-backed security forces.[26] Simultaneously, the lack of basic government services, such as access to water and electricity, has provoked widespread discontent and anti-government protests in Abyan.

Shabwa

Neighboring Abyan to the west is the Shabwa governorate. Home to the bulk of the Awaliq tribe – one of Yemen’s most powerful – local politics have historically been dominated by tribal dynamics, with tribal loyalties and considerations underlying essentially all social interaction. Central government authorities have typically had minimal purchase in the governorate. The population is mostly dispersed across rural areas and there are few large cities or towns, while the geography is a rugged mix of mountains ranges and deserts.

Upon the establishment of the PDRY in the early 1970s, the Yemen Socialist Party attempted to reduce tribal influence. The tribes resisted, resulting in regular violent clashes that eventually lead to the death or exile of the bulk of Shabwa’s leading tribal figures. The forced nationalisation of business interests across South Yemen also spurred a particularly steep decline in economic activity and living standards in Shabwa. The damage to the historical tribal social order and the concurrent failure of the socialist project eventually helped fracture many Shabwa communities.

With Yemen’s 1990 unification, swaths the governorate’s exiled tribal elite returned and quickly began to rebuild the old tribal orders, including re-establishing a range of former allegiances, grievances and tribal structures for conflict resolution. The return to the tribal power structure was facilitated through both locals’ continued esteem for these leaders and their traditional ways, as well as the central government’s continued neglect of, and inability to assert control over, most parts of the governorate. It should be noted, however, that similar to what occurred elsewhere in South Yemen, various Shabwa elites who were previously socialist party members were also absorbed into high-ranking positions in Sanaa by the Saleh regime following the 1994 civil war.

The central government’s disregard for many locals was blatantly expressed following the discovery of hydrocarbon reserves in Yemen and the establishment of the Balhaf Liquified Natural Gas terminal along the Shabwa coastline. Despite being one of the largest industrial infrastructure projects ever undertaken in Yemen, the bulk of financial benefits were channeled back to Sana’a, passing over those in Shabwa itself.

This marginalization and disassociation from the central authorities, as well as the governorate’s rugged terrain, made Shabwa an ideal location for Al Qaeda to build clandestine networks and a base of operations. For instance, Yemeni-American extremist cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, who hailed from a prominent tribal family native to the governorate, found refuge here, as did Fahd al-Quso, an Al Qaeda operative who played a key role in the USS Cole attacks. Given the Shabwa tribes’ general animosity to outsiders, however, the vast majority of AQAP fighters who have sheltered in Shabwa are themselves from the governorate, a dynamic much more prevalent than other governorates in which AQAP operates. Ever mindful of angering the governorate’s powerful tribes, AQAP also maintained a relatively light footprint despite its significant presence, working to avoid conflict with tribal elders whenever possible; this has lead them to relocate during times of increased US drone strikes in order to avoid civilian casualties and any rise in local resentment towards the organization as a result.[27]

In 2011, Ansar al-Sharia escalated operations in Shabwa and established an Islamic Emirate in the southern district of Azzan, a longstanding area of activity, thus launching its first pilot governance efforts in Yemen. Unlike in Abyan, however, Yemeni government forces and their allies did not undertake any serious military effort to dislodge AQAP from Azzan, but rather the group withdrew voluntarily in 2012 after a negotiated tribal mediation.

Like Abyan, Shabwa was also the scene of a significant Houthi incursions in 2015. Owing to widespread popular anger at the Houthis’ heavy handedness – which included demolishing the homes of prominent tribal leaders opposed to them – Al Qaeda’s presence became a secondary concern for many, with focus instead turning to forcing a Houthi to retreat from Shabwa. Once the Houthis had lost control of the governor’s capital, Ataq, and other key areas of Shabwa, local conflicts between various tribes and AQAP sporadically occurred.

The governorate remains, however, a mosaic of competing armed factions. While fighters and tribes allied to the internationally recognized government control the lion’s share of territory, other tribes allied to either the Houthis or former president Saleh continue to hold ground. AQAP and Ansar al-Sharia also maintain operational space and continue to exploit the lack of government institutions and security forces, building local clout by carrying out effective governance functions themselves and performing conflict mediation between local groups.

Looking ahead

On current trajectories in Yemen – and in the governorates of Al-Bayda, Abyan and Shabwa in particular – AQAP is likely to both deepen its local entrenchment and expand its operational capacity. The increased use of American military force alone will almost certainly fail to defeat AQAP, and will indeed likely be counterproductive to that end. The destruction and civilian casualties heavy-handed military interventions inevitably entail have already, and will continue to, alienate civilians and potential counter-terrorism allies on the ground, increase popular sympathy for AQAP and similar groups, and bolster their recruitment efforts amongst the local population.

The escalated use of US military force during the eight years of the Obama administration failed to produce more than a short-term disruption to AQAP operations. Today AQAP is arguably more powerful, resource-rich, entrenched, and operating with more institutional flexibility and adaptive capacity than ever before. There is little reason to believe that a further escalation of US military intervention in Yemen will, by itself, succeed in curtailing AQAP’s long-term ascent.

The marginalized nature of areas where AQAP has found operational space in Yemen is crucial in this dynamic. While the lack of electricity or access to water, for instance, do not inherently convert rural Yemeni civilians into jihadi militants, there is an obvious correlation between an area’s impoverishment and isolation from official institutions and its susceptibility to infiltration by AQAP. The improved delivery of basic services and necessities that often accompanies AQAP’s occupation of an area indicates that the group’s presence is largely a functional result, rather than a cause, of marginalization. This calls attention to the larger issues that have created an environment in which AQAP is able to thrive, and the fact that combating AQAP cannot simply mean killing AQAP fighters: efforts to promote local governance, to improve provision of services and, perhaps most importantly, to establish security forces that locals view as both fair and competent, will ultimately do far more to combat terrorism in Yemen than heavy-handed military policy.

Understanding the historical context and the socio-political, tribal, security and economic dynamics at play in Yemen will be crucial for counterterrorism policy makers to foresee the most likely potential outcomes of their policy choices. It will also be necessary in order to identify, and understand the utility of, potential partners on the ground – American efforts to combat AQAP in Yemen will likely be futile if they do not involve cooperating with regional partners to empower local figures on the ground in Yemen to be able to enforce security in their own areas.

Counterterrorism efforts cannot be viewed in isolation from the wider conflict. As long as the larger war continues, the belligerent parties in Yemen will continue to prioritize the war effort over counterterrorism considerations, and more importantly will leave unattended the tasks of restoring coherent governance and strengthening state institutions. Policymakers are failing to properly assess the reality before them if they view counterterrorism in Yemen and the country’s ongoing civil war as independent policy issues – regardless of American military might, as long as Yemen continues its slide into failed statehood and catastrophic humanitarian crisis, AQAP and similar groups will continue to thrive.

Farea Al-Muslimi is chairman and co-founder of the Sana’a Center, and a non-resident fellow at both the Carnegie Middle East Center and the Middle East Institute.

Adam Baron is co-founder of the Sana’a Center and a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Authors’ note: This paper would not have come to reality without the extensive editing and reviews of Spencer Osberg.

Notes:

[1] For more on the history of Yemen see Yemen Divided: The Story of A Failed State in South Arabia, by Noel Brehoney, (London: IB Tauris, 2011). [2] “Top al Qaida leader in Yemen, Saeed al Shihri, reportedly dies“, by Adam Baron, McClatchy Newspapers, January 24, 2013. [3] Charlie Hebdo cartoonist Stephan Charbonnier was placed on a hit list published by AQAP’s Inspire magazine in March 2013. [4] Ansar al-Shariah emerged in 2011 as a branch of AQAP more focused on the domestic insurgency in Yemen than international operations. While it is often described as an AQAP-front, the relationship between the two groups is somewhat ambiguous; Al Qaeda itself has a stated a policy that one can declare baya’a (allegiance) to Ansar al-Sharia without declaring baya’a to Al Qaeda. [5] “Drone Wars Yemen: Analysis: US Air and Drone Strikes in Yemen“, International Security Program, n.d. [6] “The first drone strikes of the Trump administration happened over the weekend”, Thomas Gibbons-Neff, Washington Post, January 23, 2017. [7] “Trump Administration Is Said to Be Working to Loosen Counterterrorism Rules“, By Charlie Savage and Eric Schmitt, New York Times, March 12, 2017. [8] “Nine young children killed: The full details of botched US raid in Yemen”, By Namir Shabibi and Nasser al Sane, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, February 9, 2017, and “President’s first Navy Seal raid was doomed from the start“, by Michael Evans and Richard Spencer, The Times, February 3, 2017. [9] “U.S. Air Campaign in Yemen Killed Guantánamo Ex-Prisoner“, By Eric Schmitt, New York Times, March 6, 2017. [10] See “White House Seeks to Cut Billions in Funding for United Nations“, by Colum Lynch, Foreign Policy, March 13, 2017. [11] See “Yemen’s suffering is the world’s largest humanitarian crisis today“, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, February 15, 2017. [12] From author interviews conducted with local tribal elites in Al-Bayda in the autumn of 2012. [13] “Al-Qaeda militants tighten grip on Yemeni town southwest of Sana’a“, Al Arabiya News, January 16, 2012. [14] Despite media assertions otherwise, author interviews with locals indicate that AQAP fighters largely redeployed to rural areas surrounding Rada’ and within a year were able to move with relative impunity in the city again. [15] From author interviews with residents in various areas of Al-Bayda governorate. For contemporary on the January 2013 Al-Bayda offensive, see “Yemen moves against al Qaida-linked fighters after hostage talks falter“, by Adam Baron, McClatchy Newspapers, January 28. [16] While the sectarian dynamic of the conflict gained vehemence following the Houthi conquest of Sana’a, AQAP had employed sectarian tropes well before September 21, 2014 – ones which would later be mainstreamed as the conflict intensified. As early as January 2012, when Tareq al-Thahab lead the takeover of the town of Rada, media reports noted the potential for sectarian fallout between the hardline Sunni militants and Rada’s historical Zaidi Shia presence. Also see ““Al-Qaeda” Takeover of Radaa: Saleh’s Latest Ploy?“, by Jamal Jubran, Al-Akhbar English, February 12, 2012. [17] “Trump risks deeper entanglement in Yemen’s murky war“, By Noah Browning, Reuters, February 7, 2017. [18] “Treasury Designates Al-Qaida, Al-Nusrah Front, AQAP, And Isil Fundraisers And Facilitators“, The US Department of the Treasury, May 19, 2016. [19] Hadi would, following the 2011 Arab Spring uprising, eventually replace Saleh as president. [20] Among the most fervent proponents of this strategy within the Saleh regime was his right-hand man at the time, Brigadier general Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who would, decades later following the 2011 uprising in Yemen, break from Saleh and become his adversary. [21] From multiple author interviews conducted with Sheikh Tareq al-Fadhli over several years. [22] From author interviews with locals in Aden in the spring of 2013. [23] From author interviews with locals in Aden in the spring of 2013. [24] From author interviews with Southern Resistance leaders in spring 2016. [25] “Al Qaeda militants begin to leave two Yemeni towns: residents“, Reuters, May 5, 2016. [26] “UAE-trained Yemenis recapture city from Al Qaida“, Gulf News, April 15, 2016. [27] From author interviews conducted with Shabwa tribal elites in the spring of 2013.