Summary

In February, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations stated that “Yemen is facing the largest food security emergency in the world”, and estimated that the country’s domestic reserves of wheat would be completely exhausted by the end of March 2017.

The UN human rights commission raised credible reports that war crimes were committed by both the main warring sides during battles for the Red Sea port town of Mukha. These battles saw the forces backing Yemeni President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi capture the town from the Houthi movement and its main ally, former President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

The infighting that broke out in January between groups backing President Hadi continued through February in the cities of Taiz and Aden, while resource and revenue scarcities helped fuel tensions within the Houthi-Saleh alliance and between the Houthi-Saleh alliance and populations in areas they control.

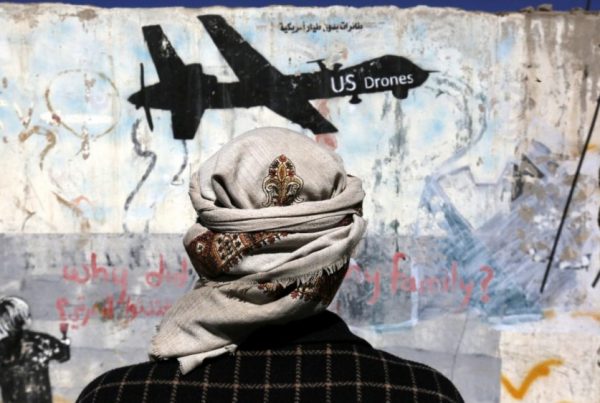

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula continued to exploit the chaos brought on by the conflict, the humanitarian crisis and the country’s economic collapse to improve its domestic position, and throughout February stepped up attacks against both main warring sides.

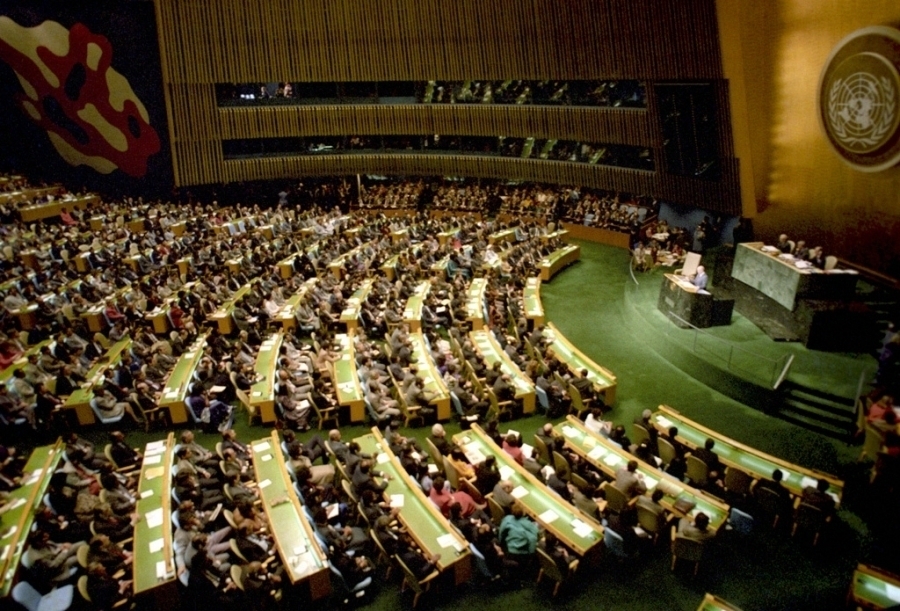

Meanwhile, UN Secretary-General António Guterres, in his second month on the job, visited the Gulf region and after meeting with regional governments publicly reiterated his support for the UN Special Envoy for Yemen and his efforts to mediate a peaceful resolution to the war.

At the UN

Continuing war crimes reports

On February 10, the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a statement citing “extremely worrying reports” that over the preceding two weeks there had been numerous violations of international humanitarian and human rights law in the battle for the port city of Mukha. This follows on the heels of the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen’s report on January 27, which stated that over the past two years there has been clear evidence of widespread and systematic violations of international law by all sides in the conflict.

The human rights commission’s February statement noted that the warring sides had issued civilians in various areas of Mukha city contradictory commands – with forces loyal to President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi ordering them to evacuate as those allied with the Houthi movement demanding they remain – with credible reports then emerging from Mukha of fleeing civilians being shot by Houthi snipers and others who remained being killed in their homes by airstrikes from the Saudi-led military coalition backing Hadi.

In a statement, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein said: “Civilians were trapped and targeted during the Al Mukha fighting. There are real fears that the situation will repeat itself in the port of Al Hudaidah, to the north of Al Mukha, where air strikes are already intensifying. The already catastrophic humanitarian situation in the country could spiral further downwards if Al Hudaidah port – a key entry point for imports into Yemen – is seriously damaged.”

Zeid noted the “alarming frequency” with which incidents of possible war crimes had been reported over the last two years of conflict, and to “break the climate of impunity in Yemen” he reiterated his call for an independent international investigation – a proposal that has been put before the Human Rights Council several times over the past two years and each time was rejected by Saudi Arabia and its allies on the council, including the United States and the United Kingdom.

At a press briefing on February 28, Ravina Shamdasani, spokesperson for the UN human rights commission, said the UN had verified almost 1,500 cases of children being recruited as soldiers since March 2015. She urged all sides in the conflict to refrain from such practices, which are strictly forbidden by international humanitarian and human rights law and may amount to war crimes in cases where the child is under 15 years old. Shamdasani added that “the numbers are likely to be much higher as most families are not willing to talk about the recruitment of their children, for fear of reprisals.” She said most of the cases they had uncovered related to recruitment by Houthi-affiliated “Popular Committees”.

Diplomatic maneuvering

On February 10, a high ranking Houthi official submitted a letter to the newly-minted UN Secretary-General António Guterres requesting that he not renew the term of the current UN Special Envoy for Yemen Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, who was appointed by former Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon in April 2015. The letter claimed Ould Cheikh Ahmed has shown a “lack of neutrality”, was biased toward the Saudi-led coalition and urged the UN to investigate a Saudi-led coalition airstrike on a funeral gathering in Sana’a in October 2016 that resulted in hundreds of casualties.

In a direct rebuff to the Houthi request, two days later the Secretary-General, speaking at a press conference in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, said: “Our envoy has my full support and I believe that he is doing an impartial work [sic], that he is doing it in a very professional way and independently of what other people may think.”

Guterres also noted during the press conference that Saudi Arabia was “an important pillar of stability in the region.” The Secretary-General was in Riyadh as part of his first major international tour in his new position, a trip which also took him to Oman, Qatar and Egypt. While also discussing the situations in Libya and Syria with regional leaders, Guterres noted that a specific priority on his trip was to support Ould Cheikh Ahmed in his attempts to restart peace negotiations in Yemen. In the nearly two years he has been Special Envoy, Ould Cheikh Ahmed and his small team of staff – relative to other comparable UN missions – have failed to secure a meaningful de-escalation of hostilities or even establish a framework the warring parties could agree upon by which further peace negotiations would proceed. Indeed, President Hadi rejected outright the last “roadmap” to peace the Special Envoy proposed in December 2016.

On February 17, the internationally recognized government of Yemen’s representative to the UN then submitted a request to the Security Council asking that the Houthis and allied forces of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh be officially designated as “terrorists”, citing a Houthi attack in January on a Saudi vessel off Yemen’s Red Sea coast.

Also last month, foreign ministers from Oman and the “Quad” – the multilateral diplomatic initiative that includes the US, UK, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – met with the UN Special Envoy for Yemen in Bonn, Germany, though no significant public statement was forthcoming following the mid-February meeting. It should be noted that during the latter half of 2016, US Secretary of State John Kerry and the US were forcefully leading the Quad’s efforts to support the Special Envoy in bringing the warring parties to commit to a peace process. The new US administration inaugurated in January has yet to articulate a Yemen policy – something other western diplomats have said has effectively placed the peace process on hold – though indications are that going forward the White House will be more sympathetic towards Saudi Arabia and more aggressive toward Iran and the Houthis.

Meanwhile, representatives from several security council member states noted to the Sana’a Center last month that the lack of a diplomatic presence in Yemen – with only Iran and Russia maintaining functioning embassies in the country – is creating significant challenges for them to independently source information and analysis regarding evolving dynamics on the ground. This has created a situation in which many member state’s primary information sources are largely the UN’s own agencies. President Hadi’s calls for the UN and foreign governments to reopen their offices and embassies in Aden have gone unheeded, likely largely due to the general security vacuum that exists and the Yemeni government’s own tenuous presence in the city.

On the ground

Pro-Hadi forces capture Mukha, AQAP expands attacks

Fighting between the main warring parties occurred along frontlines across Yemen throughout February, as did Saudi-led coalition airstrikes within Houthi-Saleh held territory. Despite the warring parties’ frequent claims of grand victories in sympathetic media outlets, in most areas a relative stalemate and war of attrition prevailed. The major exception to this was along Yemen’s Red Sea coast, where Hadi-aligned forces, heavily supported by coalition airpower and naval bombardments, have succeeded since the beginning of 2017 in making progress in the western areas of Taiz province.

Intense battles in the later half of January and through February have resulted pro-Hadi fighters in the area seizing control of most of the port town of Mukha from the Houthi-Saleh alliance, with the apparent aim to continue northwards to Hudaidah, the most significant port the Houthis and Saleh still control. Following the loss of Mukha, Houthi allied fighters withdrew towards the town of Khokha, north of Mukha, and to areas around Khalid Bin Al-Walid military base to the east.

On February 22, Hadi Government appealed for international assistance to help in demining operations, notably around Mukha, where Houthi/Saleh forces heavily deployed landmines and the fighting has left untold numbers of unexploded ordnance. The same day, Houthi-Saleh rocket fire toward Mukha killed Deputy Chief of Staff General Ahmed Said al-Yafei, one of President Hadi’s most senior commanders and an architect of the Red Sea offensive. (His replacement had yet to be named by end-February.)

Later the same week the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that some 25,000 people – the vast majority of Mukha’s population – had fled the town due to the fighting, and that “the main hospital is functioning at minimum capacity and there are reports of scores of dead bodies in the street.”

Among the many military actions elsewhere in the country in February were the intermittent Saudi-led coalition airstrikes around Sana’a. Early in the month several of these struck ostensibly military targets, however on February 15, OCHA reported that airstrikes on a funeral gathering in the Arhab district killed six women, one child, and wounded at least 15 other civilianss.

Zone of control in Yemen as of February 28, 2017

Meanwhile, AQAP stepped up its attacks against both pro-Hadi forces and the Houthi-Saleh alliance throughout February. In the first 10 days of the month AQAP fighters captured three towns in northern Abyan and briefly occupied several neighbourhoods in the city of Lowder, assassinated two Houthi-Saleh commanders in Ibb governorate and then clashed with Houthi-Saleh forces in the governorate’s al-Sayyani and Udayn districts.

Through mid-February AQAP was suspected of being behind a rocket attack against UAE-affiliated forces in the capital of Hadramaut governorate, Mukalla, and responsible for the assassination of a local official and three others in the city of Araq, Shabwa governorate.

In the last seven days of the month AQAP ambushed a government convoy in the Lawder district of Abyan governorate and captured military hardware, attacked a Houthi-Saleh convoy in Qayfa, al-Bayda’ governorate, with an improvised explosive device, ambushed other Houthi-Saleh units in the town of al-Zuqab, destroyed a police complex in Shabwa governorate and initiated an attack on the government-held Najda military base in Abyan governorate with a massive a suicide car bomb. On the last day of February Southern Movement leader Hassan Hanshal al-Awlaqi was then assassinated in Ataq, in what is also suspected to be an AQAP operation.

Infighting amongst pro-Hadi forces

In the last week of January, Salafist groups in Taiz seized control of the city’s main administrative institutions in areas outside of Houthi-Saleh control. This sparked intermittent street battles since between the Salafists and other groups, primarily Islah (the Muslim Brotherhood Party in Yemen). In the almost complete absence of government institutions capable of policing the city, areas of Taiz under government “control” have experienced severe insecurity and the rise of criminal gangs. Notable events last month included the February 13 assassination attempt against an Islah leader and the February 23 attack on the market in the al-Koba area – gunmen opened fire on civilians, killing four and wounding nine, in what was reportedly a dispute between competing extortion rackets operating in the market.

On February 25 dozens of residents took to the streets to protest the lack of security, with the relative decrease in security-related events in government-held areas towards the end of the month being attributed to AQAP, whose affiliates were able to mediate between the various anti-Houthi groups.

Meanwhile in the government-held southern city of Aden, soldiers protecting the airport, under the command of Saleh al-Omeri, shut down the facility for part of February 10 in protest of not having received their wages. The following day President Hadi sent presidential guard units to the airport to replace al-Omeri’s soldiers, resulting in a gun battle between the two when the latter refused to step down. The situation escalated when Salafist units in the area attempted to reinforce al-Omeri – both of whom receive substantial backing from the United Arab Emirates – after which an Emirati helicopter gunship opened fire on a Presidential Guard vehicle, killing multiple soldiers.

Negotiations followed, the fighting subsided and the airport officially reopened the next day with al-Omeri’s men still in control, though Yemenia Airlines continued to cancel or reroute flights to and from Aden. This incident is emblematic of the deep rifts that have developed within the military forces fighting against the Houthi-Saleh alliance, and specifically between President Hadi and the UAE. Shortly after the incident Hadi was in Riyadh, reportedly to discuss the airport battle with Saudi and Emirati government representatives.

Houthi-Saleh tensions

Throughout February disputes within the Houthi-Saleh alliance continued to prevent the appointment of a successor to Ali al-Jaifi, the head of the Republican Guard who was killed in the Saudi-led coalition airstrike on a funeral gathering in Sana’a in October 2016.

Later in the month tension also arose between the two allies in the Ibb governorate when Houthi affiliates began issuing local building permits, directly contradicting and overstepping the authority of ministry officials in Sana’a loyal to Saleh. It is important to note that, as the severity of the economic crisis has continued to intensify, licensing and official permits have become an important source of cash, though Saleh’s long-standing patronage networks within the state bureaucracy are now competing with new, parallel Houthi networks for these revenues.

In Houthi-controlled Dhamar governorate, south of Sana’a, escalating local frustration and resentment against the Houthis led to armed clashes in the Utma district, with Houthis fighters being captured and killed in skirmishes in the latter half of the month. The Houthis responded to this resistance by kidnapping prominent locals who had been vocal in their opposition, and destroying the homes of others. Numerous reports suggested the Houthis were employing similar methods of repression against the local population in various areas of the Taiz governorate.

Continuing humanitarian crisis

UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization declared in February that “Yemen is facing the largest food security emergency in the world”, and that “[c]urrent estimates indicate that existing supplies of wheat in the country will last until the end of March 2017.” This followed the February 8 UN launch of an international appeal for aid amounting to $2.1 billion to “provide life-saving assistance to 12 million people in Yemen in 2017”. It is the largest ever consolidated humanitarian appeal for Yemen.

In announcing the appeal OCHA noted that the conflict has left 18.8 million people – more than two thirds of the population – in need of humanitarian assistance; some 10.3 million Yemenis are acutely affected and require “some form of immediate humanitarian assistance to save and sustain their lives.” This includes food, healthcare, clean water and protection. Some 3.3 million people, including 2.1 million children, are acutely malnourished.

A February 21 UN report stated that since 2015 the conflict has displaced some 3 million Yemenis, but that some one million have since returned. “It’s testament to how catastrophic the situation in Yemen has become, that those displaced by the conflict are now returning home because life in the areas to which they had fled for safety is just as abysmal as in the areas from which they fled,” said the UNHCR’s Country Representative for Yemen, Ayman Gharaibeh. “Those attempting to return face tremendous challenges… They often return to homes that have been damaged, in areas lacking essential services. They still need humanitarian aid and are often forced to flee their homes again. These returns cannot be viewed as sustainable.” (Among those most recently displaced are some 44,000 people who have fled their homes because of the surge of fight in Taiz province, including those from Mukha.)

On February 26, The Ministry of Public Health and Population in Yemen released figures showing that since the end of January 2017 there had been 1,610 new suspected cases of cholera reported, including 4 deaths. The report said there appeared to be a decline in the rate of new cases per week, with 80% of the new cases in this latest report located in 13 districts in the Al Hudaidah, Dhale, Hajjah and Taiz governorates. In a subsequent briefing spokesperson Christophe Boulierac from the UN Children’s Fund said every 10 minutes a Yemeni child under the age of five is dying from a preventable disease – such diarrhoea, pneumonia or measles – due to almost half the country’s medical facilities being out of servicee.

The dangers and difficulties aid agencies face while trying to operate in Yemen were also made apparent in two high profile incident in February. On February 14, six aid workers and a driver for the Norwegian Refugee Council were arrested by Houthi-Saleh forces while attempting to distribute aid in Hudaidah city; they were released again a week later “in good condition”, according to the NRC, which called the incident a “misunderstanding.” On February 28, UN Emergency Relief Coordinator Stephen O’Brien – after having secured guarantees of safe passage from all parties – had his convoy turned back from entering besieged areas of Taiz at a Houthi-Saleh checkpoint. In a statement OCHA reported that: “O’Brien was extremely disappointed that humanitarian efforts to reach people in need were once again thwarted by parties to a conflict, especially at a time when millions of Yemenis are severely food insecure and face the risk of famine.”

Currency volatility and the loss of food reserves

Currency volatility was apparent last month, with the Yemeni rial falling as much as 20% in value against the US dollar in black market trading through the first half of February, before market interventions in both Sana’a and Aden helped the domestic currency to regain lost ground and stabilize. The interventions included the Houthi-Saleh authorities forbidding fuel and food importers from purchasing foreign exchange on the market for 30 days, and implement new measures against currency speculation. In parallel, the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) governor in Aden, Monasser Al Quaiti, met with exchange companies and banks to discuss currency stabilization, assuring them that the Aden-based Central Bank was soon to receive significant foreign exchange support.

Currency stability is a critical issue for Yemen, given that previous to the conflict the country imported 90% of its basic food stuffs. Worryingly, however, was that through February Yemen’s largest bulk wheat and rice importers reported their continued inability to access import guarantees from the CBY, a primary driver of the country’s food insecurity. In an effort to help make up for the loss of these commercial food imports and stave off famine, a World Food Program chartered cargo vessel was able to dock at Hudaidah port on March 1, where it planned to offload 14,000 metric tons (mt) of wheat, before heading to Aden to offload another 6,000 mt.

Imports are being further hampered, however, by the challenges facing Yemen’s ports. Hodeidah, along the Red Sea coast, was previously one of Yemen’s busiest ports but had its offloading capacity severely curtailed by damage from Saudi-led coalition airstrikes early in the conflict – despite this it and the smaller Saleef port to the north continue to import the majority of Yemen’s bulk food items such as wheat and rice. Hudaidah’s port facilities were also briefly forced to cease operations last month by the coalition, which demanded cargo ships offload in Aden instead; insecurity in the southern port city, and security and logistics challenges transporting goods around Yemen from Aden, however, continue to make it unattractive for importers.

In the later half of February, the Houthi-Saleh authorities imposed a customs duty on all commercial trucks entering Houthi-Saleh controlled governorates, effectively doubling the customs duty already paid by traders at the ports. Almost immediately there were reports from Sana’a that numerous pharmaceutical drugs had risen in price, some by as much as 35%. On February 22, the Yemeni Chamber of Commerce issued a letterprotesting the new duty fee and threatening to redirect their business to markets in Hadi controlled areass.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of Yemen’s public sector workers – who made up one-third of Yemen’s employed workers pre-conflict – continued to go without their wages in February, as they have since August 2016, perpetuating the collapse of public services and the slide into extreme poverty for millions of people.

In a sign that some economic relief may be on the horizon, President Hadi announced on February 20 that the Saudi government has agreed to deposit $2 billion as currency support at the CBY in Aden, and offered billions more in reconstruction aid to government-held areas.

As of March 2, 2017, this financial support had yet to materialize.

In brief

- The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) had, as of March 2, received 2.3% of the USD $2.1 billion it has appealed for to implement its humanitarian response plan for Yemen in 20177.

- In the month of February, 38 vessels applied for clearance from the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM); 27 requests for clearance were issued certification and the average time to issue clearance was 34 hours, an average of six hours less than the month before. A total of 413,343 metric tons (mt) of cargo was approved through the UNVIM in February, consisting of 207,906 mt of food, 73,782 mt of fuel and 131,655 mt of general cargo. This is a decrease by a total of 153,003 mt of cargo from the month before.