In November 2011, conflicting Yemeni parties signed an international initiative to lead the country out of its crisis. It later came to be known as the Gulf Initiative, as it was adopted by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) — with the exception of Qatar, which pulled out of the project because former President Ali Abdullah Saleh refused for Doha to be involved.

Everyone was optimistic that the initiative would spare the country a civil war, rather than resolving other national problems. It was not long before concerned parties started to implement the terms of the initiative. Parliament convened to pass a law granting immunity to the former president and his regime from any accountability and prosecution, against the backdrop of the decisions taken during the period of his rule. The government of national consensus was then formed, between the General People’s Congress (the current ruling party) and the opposition parties in December of the same year.

The election of the current president, Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi, was just for show. He did not have any rivals running against him. After Hadi formally received the reins of power, a pivotal stage in the political transition began. A number of senior leaders in the army were sacked and new ones were appointed instead.

But the Gulf Initiative is trying to delay the conflagration of the Yemeni situation rather than resolving national problems, as was expected. Hadi, whom almost all political forces supported, does not hold the ultimate decision-making power, or at least is not able impose it on the ground except by two means. One of those two means is international intervention. The other is to trigger a war, which the Gulf Initiative was created to end. But this impression faded when Hadi sacked the main army heads and the most prominent symbols of military horror: the leader of the Republican Guard and the leader of the 1st Armored Division. Those two men have divided the army into two parts, each loyal to one of them. They were removed from their posts and the Yemeni army’s units were redistributed on a different basis. But the division is not completely over.

The national dialogue

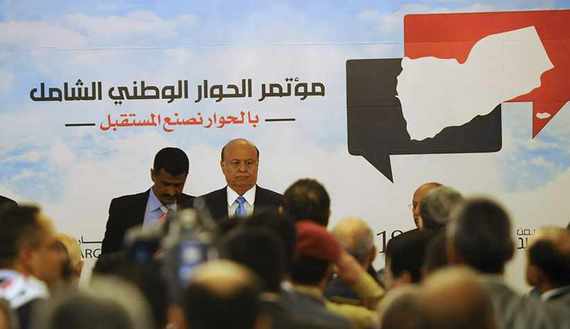

The mechanism set by the Gulf Initiative to take Yemen out of the complexities of its interrelated problems (it seems that this mechanism was added to the original initiative) was that fuzzy invention called the “comprehensive national dialogue,” in which the parties to the conflict sit and debate the country’s problems and find the solutions that they deem appropriate.

As the Gulf Initiative evolved, so did the idea of the dialogue. Rather than limiting the dialogue to the fundamental problems that need the consensus of the parties, it was expanded to include discussion about what the future would look like, a matter about which participants in the dialogue disagree.

After being postponed for months, the dialogue started on March 18, 2013, and was supposed to end on Sept. 18. But that did not happen. The deadline was extended. And the dialogue has been going on for three months past its original deadline, or 50% beyond its original length.

Despite that, it has not produced what the Yemeni people want. From time to time, the differences between the political forces become public and are thus an additional burden on the lives of the citizens, who already have enough problems. These already existing problems were not alleviated by the dialogue or by the national unity government, except perhaps for the emergence of new faces in public life and the mass media.

Thus, like Yemeni unity in 1990 and the repeated Yemeni revolutions, the national dialogue seemed like an opportunity for the Yemenis to solve their own problems, only for the dialogue to turn into a problem in itself. So the big and most worrisome question in Yemen is now “how will the dialogue end? And how can it end without sparking a civil war?”

Solutions without problems

After the distribution of the teams and the duties of the national dialogue conference, it has become customary to hear about reaching certain solutions (as theoretical outputs) to certain problems that weren’t calling for a solution in the first place, or at least were not part of the dialogue’s priorities, such as quotas of women, how to preserve traditional heritage or the constitutional article about the source of legislation in the country.

At the other extreme lie the real problems, firm and unmoving, without a practical development. The roots of the Southern issue, which is the mother of all issues, have seen some proposals on how to resolve them (some of which were implemented and others are in the process of implementation): such as the problems of land and of those laid off involuntarily from their jobs. But the fruits of this issue, in its final form, did not turn out to be a clear and agreed upon prescription, and its solutions are mere conflicting proposals. Despite that, some in conference profess reaching a new formula based on federalism.

Will federalism by a real solution to the Southern issue?

This is another matter. Federalism is a medication that relieves the symptoms of an unidentified disease.

Some major forces — such as the General People’s Congress and the Reform Party — have rejected federalism. But the international trend, which seems to be in support of federalism (at least as represented by UN envoy Jamal bin Omar), has turned the rejection into a disagreement over the new shape of the state. That shape may harm national unity and is a red line for the parties who consider federalism to be a threat to the country’s unity.

Practically, federalism may represent a solution to a problem that was mainly due to the weakness of the central state, corruption and the lack of social justice. The state’s form was not the crux of the problem. At the same time, not even the number of regions in the new federal state was agreed upon. As to how to divide the country into regions and on what basis — economic or geographic, according to population or water availability (which is the most serious issue facing Yemen in the short and long terms), and so on — that issue may need experts and technicians more than dialogue between rivals.

The other problem is how to reconcile two opposite inventions and convert them into a reasonable medical prescription, although it may end up looking closer to chemotherapy. Transitional justice was established as one of the solutions to the national dilemma that then turned into a dilemma in and of itself. Over the past two years, the text for a transitional justice law was not agreed upon, especially with the presence of a law that represents one of the pillars of the Gulf Initiative: the immunity law granted to the former president and his regime.

Annulling the immunity law will give Saleh’s General People’s Congress a golden chance to rid itself from the commitments imposed by the Gulf Initiative. If the party remains in power, it will also be a golden chance to obstruct the law on transitional justice.

Simultaneously, there was a new invention called the law on political isolation, which excludes prominent figures from participating in political life because of their involvement in the former regime. This expression, however, is vague; the majority of figures who are positively or negatively active were part of that regime. This law was used to escape the trouble of immunity. The law, however, was strongly opposed by the General People’s Congress and was transformed into a series of detailed conditions imposed on these figures, limiting their abilities to run for office or assume key positions. This also has yet to be settled.

What’s next?

Recently, a new invention came from outside the rules of the game. The interlocutors, or inventors, were transformed into a constituent assembly replacing the parliament and the Shura Council. The mandate of the assembly, which ends in February, will be extended. This invention, however, is still opposed mainly by the General People’s Congress.

What is next? Where is Yemen heading? This question has not yet been answered by the interlocutors and was not even included in their various innovations.

The vision may become clear in December when the backstage issues become public. It seems like the culture of political deals is ongoing and it is hard to foretell its prices, merchandise and traders. Does Yemen have time to wait? Probably not. It is a country running out of water, resources and time.