I have encountered two separate Yemens this past week: the one portrayed in Western media outlets and the other reality of living in Sana’a. One was rife with conflict and insecurity, the other associated with the navigation of the capital’s gridlocked traffic. Yet the two Yemens collided in a visceral way for most people.

The al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) plot, described vaguely by President Obama as a “threat stream”, and the subsequent US embassy closure in Sana’a were far from the minds of most Yemenis. Most were more preoccupied with the approaching conclusion of Ramadan, the Eid al-Fitr celebrations and the political direction of the nation, most notably the United Nations-backed National Dialogue Conference, which aims at drafting a new constitution before elections in February.

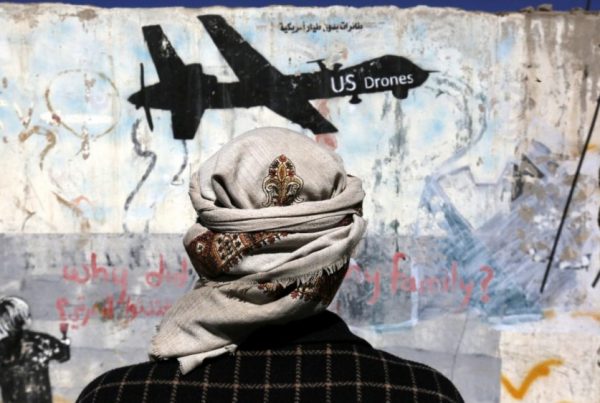

Then, the calm and pre-Eid excitement in Sana’a was punctured on Tuesday morning, two days before the end of Ramadan. Sana’a residents were shocked and terrified by the strange buzzing sound that accompanied an unfamiliar aircraft hovering above the capital, which followed a morning drone strike in the Hadramaut region.

The buzzing induced terror in residents, and speculation between friends and family as well as on social media. The capital was abuzz with concern about drone strikes in different sections of the city. The terror was unquantifiable.

The resumption of US drone strikes in late July unleashed terror in the regions that were most affected: Hadramaut, Abyan and Ma’rib. Photos of the plane circulated on social media. In response, experts from around the world assured me and other Yemenis that this was “merely” a US P3 surveillance plane and not an actual drone. It was remarkable to witness foreigners assure us that an actual strike drone was not overhead, as if that was meant to provide some comfort.

In less than a week, the US conducted eight drone strikes in different parts of the country – a record in Yemen. The myopic focus of the world’s media on these strikes only seemed to fuel the drone activity and, by extension, drive insecurity for most Yemenis.

After the eighth drone strike, I sat helpless in my room reading a message from a friend in the eastern province of Hadramaut. Our last five phone calls had focused on the drone strikes. The frustration and disappointment I felt was nothing compared to what my friend or people like him were going through. I wanted to know why more people were not reporting what was happening and what the drone attacks would change. They will just be new statistics added to the superficial reporting about Yemen.

Nobody is yet sure of the identities of those killed in the attacks. But I knew that media would report “suspected militants” were killed.

We have yet to read the real truth about the killing of five militants in Wessab, my home village, in April. The attack was included in my testimony before the US Senate the same month as a writer and human rights campaigner. Speaking to families of the people killed, I found what had happened was the opposite of what we were being told.

These were not militants who were killed. The four men were just locals who did not even know that the guy they were with was the target of a US drone. One of them was waiting for the military college to open. His father told me his son had wanted to join the military and work to secure our country and combat bad people – the targets of the Americans.

He asked me if what I did would change anything. A world of disappointment was in his eyes when I told him I did not know. My testimony may have brought too much hope to too many people. It did nothing to change the problem other than elicit a disappointing speech by the US President in an attempt to absorb the local and international anger against the use of deadly drones that kill my countrymen, and supposedly secure America.

Contrary to US claims about the conditional use of drones – that they should be used when the cause is just – the recent strikes have made them more than just a tool to eliminate al-Qa’ida leaders.

The US is running to drones every time its counter-terrorism efforts fail. On each occasion the public rage against al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula grows and its image is tarnished, and the US – via drone strikes – restores it again. In its recent actions, the US has become al-Qa’ida’s public relations officer.

Who else, other than al-Qa’ida, would benefit from the sudden, ill-thought-out and unneeded evacuation from Yemen by the US? If al-Qa’ida’s main goal is to spread fear, this has given it a free shot at doing just that.

If the threats the US talks about are real, why would it not leak the content of the conversations it claims to have recorded between two senior figures, including leader Ayman al-Zawahiri? In not doing so, the US is giving al-Qa’ida a credit note for fear, and is leaving Yemen alone in its struggle.

The evacuation of US embassies has raised serious questions about the sincerity of the US commitment to fighting al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula.

Despite all of Washington’s recent commitments and actions in supporting the transition towards democratic elections in Yemen, the drones did nothing but edge Yemenis in the opposite direction. More than 10 million Yemenis remain in need of humanitarian assistance but none of that is on the tongues of policymakers in the west. Donor pledges of almost $8bn (£5.16bn) for Yemen, via the Friends of Yemen, seem nothing more than a lie.

The US comprehensive policy towards our country is comprehensive only on paper. Yemen is, once again, in the West’s view, a country where problems come from.

As the country was waiting for Eid to finish so that the US-funded and supported National Dialogue Conference could resume and eventually finish negotiations on the coming constitution, the US suddenly, via the drones, sent a message that such an entity and its delegates were much less important, and would be taken less seriously, than the shared enemy of both Yemenis and the US – al-Qa’ida.

It is obvious, as never before, that outside interference in Yemen has been intended not to create a better, democratic and stable Yemen, but instead to prevent its security problems getting worse in the eyes of pilots of drones based thousands of miles away.

The gap between the US – the US of hovering planes and deadly drones – and al-Qa’ida has actually shrunk in the eyes of many Yemenis: there is very little difference between what the two are doing to ordinary people. Innocent lives are lost due to the actions of both. They are both hurting people and distorting the image of Yemen. The only difference is that the US shapes its thinking on Yemen by studying statistics. The other knows Yemen’s history, culture, memories, sensitivities, laws and traditions. Both are now seen to destabilise the country almost equally and lead it toward less peaceful choices.

Al-Qa’ida is taking advantage of Yemen’s struggles by committing terrorism against Yemen and other countries. The US is dumping its allies, not differentiating between local people and al-Qa’ida, ignoring peaceful Yemenis and delegitimising an already weak government.

The US is forcing radical politics on susceptible young people and, worse, leaving Yemen to deal with the ensuing mess it has created.

Farea al-Muslimi is a Yemeni youth activist

Yemen’s dual foes

Al-qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula

AQAP is a militant Islamist organisation considered the most active branch of the terror network due to its increasingly weak central leadership.

Primarily active in Yemen and Saudi Arabia, it was formed in 2009 and is currently led by Nasser Abdul Karim al-Wuhayshi, who replaced Abu Yahya al-Libi when he was killed by a US drone in north-west Pakistan last year.

Drone attacks

During their early usage, unmanned aerial vehicles, more commonly known as “drones”, were unarmed. During the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 armed drones were introduced against Taliban targets. They are piloted remotely and armed with missiles of varying strength.

In the past six months the US has launched drone attacks in 27 different locations worldwide.