As Yemen’s civil war continues, extremist groups are thriving in the chaos.

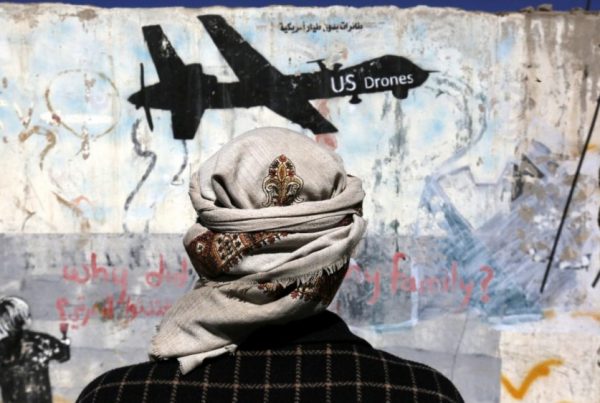

In mid-June, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) announced the assassination of its leader Nasir al-Wuhayshi in a drone strike on the city of al-Mukalla. This is the most severe blow suffered by AQAP since its establishment by Wuhayshi and Saudi member Said al-Shahri in 2009, when the two men merged the Yemeni and Saudi branches of al-Qaeda into a single group. The assassination occurred as a Saudi-led international coalition continued operations in Yemen. Weeks later, Abu Hajer al-Hadrami, al-Qaeda’s famous religious singer, was also killed in a similar drone strike, one of many that have led to the death of several prominent AQAP leaders.

Wuhayshi’s assassination may represent a turning point for AQAP. In its obituary announcing Wuhayshi’s death, AQAP was keener on explaining the details of Qasim al-Rimi’s appointment—as Wuhayshi’s successor and new leader of the group—by members of the AQAP’s Shura Council than on clarifying the circumstances of his predecessor’s killing. The successor’s appointment took place remarkably quickly in a meeting of “as many Shura people as possible” according to the statement, seemingly anticipating objections from within to Rimi’s appointment by explaining the difficult circumstances under which the choice was made.

Internal Rivalries and the rise of the Islamic State

Internal struggles within AQAP may explain why its leadership has disclosed few details about Wuhayshi’s death. For years, AQAP has been linked to a network inside Yemen known as Ansar al-Sharia, or the Supporters of Islamic Law, which seems to have been set up as a type of front organization through which AQAP attracted local support and controlled territory. One of its leaders is Jalal Baleidi, also known as Hamza al-Zinjibari. While al-Wuhayshi’s global goals were evident—he had clearly announced his allegiance to Ayman al-Zawahiri’s international al-Qaeda leadership—Baleidi’s intentions were unlear and many people close to the organization have noted the differences in the paths chosen by the two men over past years. “I am not saying that Nasir al-Wuhayshi took his orders from any Yemeni party,” a senior Western official told me, “but we actually do not know who gives Jalal Baleidi orders.”

Indeed, Baleidi’s Ansar al-Sharia did not seem to consider the U.S. its primary target. Instead it appeared to be working on the establishment of local emirates here and there, as was evident in the Abyan region during 2011-2012.

In late June, Yemeni news sites reported that Baleidi had left AQAP and Ansar al-Sharia to join the self-proclaimed Islamic State. However, in mid-August, AQAP released aninterview with Baleidi where he spoke on recent events and urged Yemeni Sunnis to fight the Houthis. It included no questions on the Islamic State.

Over the past six months, Islamic State loyalists have launched various suicide attacks in Yemen targeting mosques and civilians. The most recent attack consisted of four explosions that shook Sanaa only one day after the announcement of Wuhayshi’s death. The murder of captive Yemeni soldiers and similar operations have drawn attention to the Islamic State, much to the detriment of Wuhayshi’s organization. Contrary to AQAP, the Yemeni wing of the Islamic State doesn’t seem to have any local plans beyond violence. While AQAP has tried to win hearts and minds and pursued a policy of neutrality toward locals, the Islamic State completely disregards this strategy. Indeed, its brutality in Yemen has reached the same levels as in Syria and Iraq.

AQAP Thrives in Yemen’s Chaos

Despite the loss of leaders like al-Wuhayshi and the rise of an aggressive rival in the form of the Islamic State, AQAP is currently well placed to grow in Yemen, although not necessarily in the current shape or structure.

Central authority in Yemen has collapsed since 2011-2012, when popular protests removed longtime president Ali Abdullah Saleh. As the ensuing transition process floundered, Yemen fell apart in regional, religious, tribal, and political conflicts. A Zaydi Shia Islamist group known as the Houthis moved out of its old northern strongholds, capturing the capital Sanaa in September 2014. There is no longer a national army leadership and military units previously engaged against AQAP have fallen apart or been exhausted in other battles. The Yemeni air force collapsed when it fell under Houthi control, ending many years of airstrikes against al-Qaeda. Finally, the civil war has shifted regional attention away from al-Qaeda, as Saudi Arabia and other nations are now preoccupied with the war against Saleh and the Houthis, having launched a military intervention in March 2015.

The rise of the Houthis has also helped al-Qaeda rally support in other ways. Previously, the Yemeni army’s struggle against AQAP did not have a clear-cut sectarian dimension, although the extremist Sunnis of al-Qaeda certainly viewed it in those terms. But when the Houthis and Saleh moved south in 2014 it provoked resistance in local non-Zaydi communities and reinforced the sectarian narrative that AQAP had been trying to cultivate. Unsurprisingly, some opponents of the Houthis, Saleh, and Iran have reacted by accepting support from AQAP.

Add to this the widening circle of those oppressed by the Houthis. In 2013-2014, the ascendant Houthis expelled their old arch-enemies, the Salafists of the Dar al-Hadith religious seminary in the northern town of Dammaj. Local sources in Lahij, Aden, and Taiz confirm that these Salafis remain engaged in the fight after losing their home area. In the Jarra Mountain in Taiz, some resettled Dammaj Salafis have reportedly put up strong resistance to Houthi control. The hostility between the Houthis and the Salafi movement is certainly not a new phenomenon and the Salafis’ sectarian conflict with the Zaydis long predates the conflict, but it is worth noting that the Dar al-Hadith Salafis belonged to a different school of thought than al-Qaeda, were less prone to violence, and had generally avoided involvement with international jihadi radicalism. Now dispersed, dispossessed, and fighting side by side with AQAP against the Houthis, members of this group could easily begin to slide into the orbit of AQAP, or move to the Islamic State via AQAP.

In other words, the general situation in Yemen indicates that the phenomenon of al-Qaeda or Islamic State-style jihadism is likely to expand, whether in its current shape or in new forms and under new names. Even if AQAP itself should weaken or split following Wuhayshi’s death, more extreme factions promoting a similar ideology, like the Islamic State, will be ready to step into the void as long as there is no legitimate government in Yemen.