Ali Abdullah Saleh, the former leader of Yemen, was known as a hardy survivor of Middle Eastern politics who had ruled for more than three decades and re-emerged to play a major role in his country’s devastating civil war.

Mr. Saleh, who was killed on Monday in Yemen under circumstances that remained unclear, was a canny manipulator of Yemen’s complex tribal politics who once likened his presidency to “dancing on the heads of snakes,” but his Machiavellian skills and good luck finally ran out. Aides said he died after an explosion at his home in Sana, the capital. Yemen’s Houthi rebels, his onetime allies in the war, said they had killed him in an ambush in the desert.

On Saturday Mr. Saleh had publicly broken with the Houthis, calling on Yemenis to “defend the nation” against them. That move in a lifetime of juggling alliances proved to be his last.

Mr. Saleh waved to supporters at a campaign rally in Sana in 1999, one day before voters participated in the Arabian peninsula’s first direct presidential elections. CreditRabih Moghrabi/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

By most accounts Mr. Saleh was 75 at his death, though for years his official biography made him four years younger. It was not the only flexibility with the facts that he had shown in an eventful lifetime.

His long tenure as the leader of the poorest Arab country, which suffered periodic warfare and became a hotbed for Al Qaeda, left an undoubted mark. But he was universally seen as corrupt and unprincipled, interested mainly in wealth and power for himself and his relatives, whom he installed in powerful posts.

“It is a tragic end for a tragic 33 years of misruling Yemen,” said Farea al-Muslimi, a Yemeni scholar and chairman of the Sana Center for Strategic Studies. He compared Mr. Saleh to Saddam Hussein and Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, and said that Yemen, like Iraq and Libya, had descended into chaos in part because of Mr. Saleh’s failure to build durable institutions while in office.

Gerald M. Feierstein, who met Mr. Saleh frequently as United States ambassador to Yemen from 2010 to 2013, called him “completely untrustworthy.” But he said some Yemenis would favorably compare the relative stability of their country during much of Mr. Saleh’s rule, from 1978 to early 2012, with the current violence and breakdown.

“The positive is that he did kind of hold the place together,” Mr. Feierstein said, showing “a sort of political mastery that moved Yemen forward in some ways,” including on education and health.

But Mr. Saleh, he said, “was a kleptomaniac who stole billions, perhaps tens of billions of dollars, over the years.” He based his rule on a personality cult, Mr. Feierstein said, and so “the government, the judicial system — none of it was able to function after he left office because it was built around him and his family.”

From right, the grand sheikh of Al-Azhar, President Saddam Hussein of Iraq, President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, King Hussein of Jordan and Mr. Saleh at Friday Prayer in 1989 during the Arab Cooperation Council in Alexandria, Egypt. CreditMike Nelson/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

In the later years of Mr. Saleh’s rule, his arid, impoverished country of 28 million people attracted outsize attention from the United States as a potential source of terrorist attacks by the Qaeda branch based there, known as Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

The so-called underwear bomber who tried to blow up a Detroit-bound airliner in 2009 had been trained and dispatched from Yemen. Bombs hidden in printer cartridges and loaded on commercial cargo flights were intercepted on the way to Chicago the next year.

Mr. Saleh appeared to relish the leverage that the terrorist menace gave him, cheerfully exploiting his country’s problems in his petitioning for outside aid. According to a diplomatic cable released by WikiLeaks, he once offered all of Yemen’s territory for American counterterrorism efforts and agreed to keep lying to his people about American missile strikes on Al Qaeda.

“We’ll continue saying the bombs are ours, not yours,” Mr. Saleh said to Gen. David H. Petraeus.

Mr. Saleh’s two immediate predecessors had been assassinated less than a year apart, and when he came to power in 1978, few thought he would last long. But he used formidable negotiating skills, as well as patronage, payoffs and sometimes force, to fend off challenges.

He ruled North Yemen until 1990, when he joined the south and north to form the Republic of Yemen. He survived a civil war in 1994, won a flawed vote in 1999 as Yemen’s first directly elected president and, with the help of sons and nephews in important security posts, became the longest-serving ruler in modern Yemeni history.

Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi of Libya, center, leaning on President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, right, and Mr. Saleh in 2010 at a summit in Sirte, Libya. CreditKhaled Desouki/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

In balancing rival tribes, Islamists, socialists, southern separatists and pushy foreigners, “he was like one of those jugglers with the plates spinning on the sticks,” said Barbara K. Bodine, the American ambassador to Yemen from 1997 to 2001.

“He kept all the plates in the air,” she said, calling it “a considerable political achievement.”

Mr. Saleh sometimes showed a curiosity and willingness to learn, Ms. Bodine said. Once, when she agreed to speak to Yemenis holding a conference on domestic violence — a potentially volatile topic in a conservative Muslim society — Mr. Saleh got word of the event and summoned her.

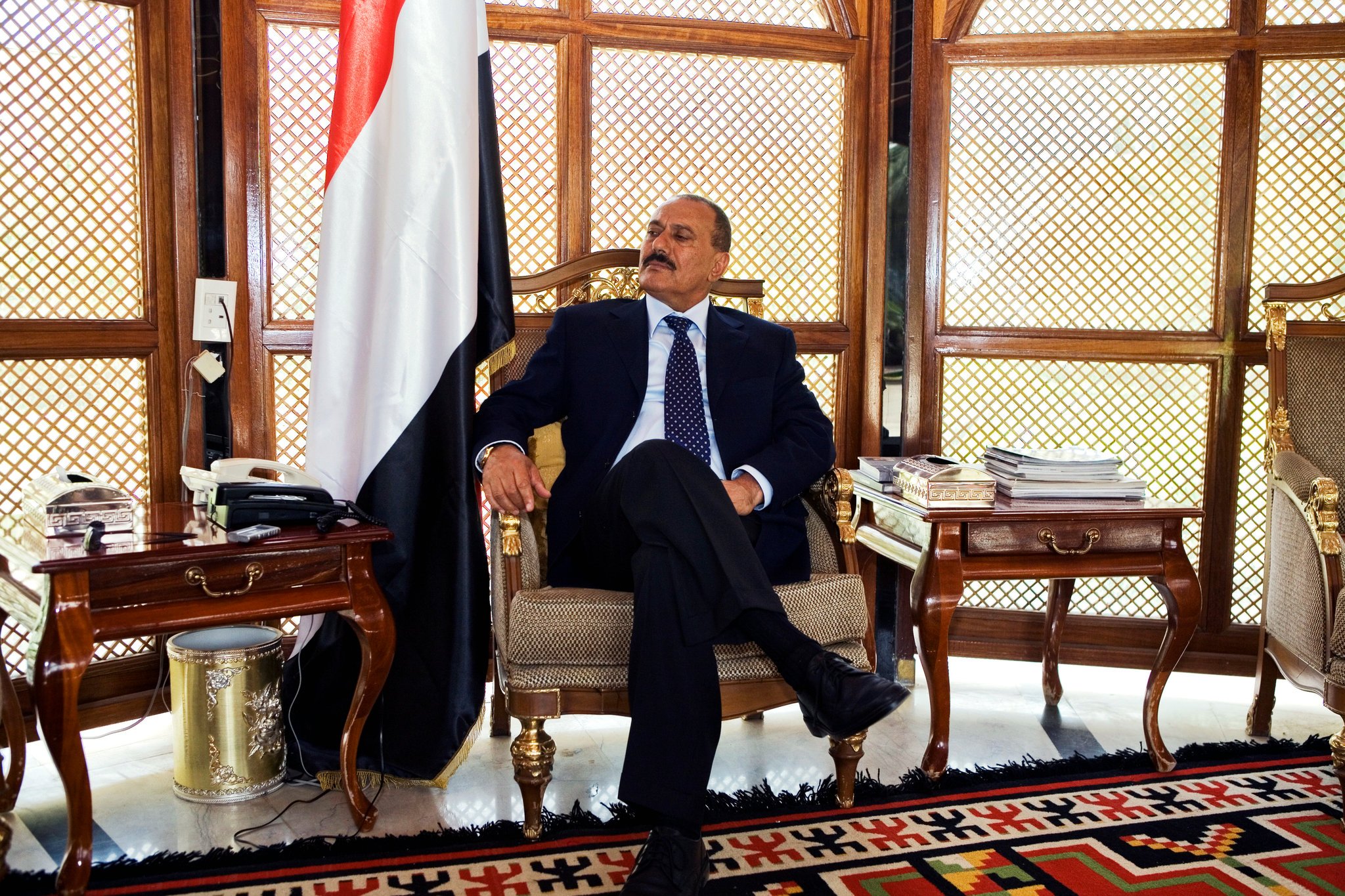

“He was sitting in one of his gazebos, and he said, ‘Tell me about this issue,’ ” she recalled. “We proceeded to have a three-hour discussion on domestic violence and the proper role of the state in intervening in relations between husband and wife. He asked, ‘What does a domestic violence shelter do?’ He didn’t lecture. He was really trying to understand.”

Mr. Saleh’s staying power was challenged when the pro-democracy fervor that had ousted the leaders of Tunisia and Egypt reached Yemen early in 2011. There were months of mass demonstrations, provoking him to sanction violence against protesters, which cost him support as senior military and government officials and diplomats defected.

Pressured at home and abroad to leave the country, Mr. Saleh responded with pugnacious defiance and stalling tactics, promising to step down and then reneging at the last minute.

President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi of Yemen, left, watched as Mr. Saleh held the country’s flag during Mr. Hadi’s inauguration in Sana in 2012. CreditSamuel Aranda for The New York Times

When the mosque in the presidential palace was the target of a bombing in June 2011, Mr. Saleh was incorrectly reported to have been killed. He suffered severe burns and got medical treatment in Saudi Arabia and the United States. He gave up the presidency in February 2012 only after months of pressure from armed tribal opponents, street protests and the international community.

Still, he held fast to tribal networks and continued to exercise power behind the scenes, undermining the rule of his former vice president and successor, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi. When the Houthi militia, which Mr. Saleh had repeatedly attacked in previous years, swept into the capital and other major cities, he surprised many Yemenis by forming an alliance with their Shiite fighters against Mr. Hadi, who was backed by Saudi Arabia. Some saw the hand of Iran behind the Houthi-Saleh alliance, which lasted from 2014 until last week.

Ali Abdullah Saleh was born into the Sanhan tribe in Bayt al-Ahmar, a farming village in North Yemen. Like many Sanhan tribesmen, he joined the military as a teenager with less than an elementary school education. A protégé of Col. Ahmad Husayn al-Ghashmi, he supported a military coup in 1974 that led to his appointment in 1975 as military commander of Taiz Province.

Supporters of Mr. Saleh, seen in posters, who were allies of the Shiite rebels known as Houthis, attended a rally to mark the first anniversary of the Saudi-led military campaign against them, in Sana in 2016.CreditHani Mohammed/Associated Press

In 1977, the military ruler, Ibrahim al-Hamdi, was assassinated, and Colonel Ghashmi assumed power.

“Saleh clearly supported the assassination, and by some accounts he quite literally had a hand in it,” said Robert D. Burrowes, a retired professor at the University of Washington who had traveled regularly to Yemen since 1975.

Colonel Ghashmi was assassinated less than a year later, opening the way for Mr. Saleh to take power.

“When he came to power, people laughed at him,” Professor Burrowes said. “He was regarded by many Yemenis as a lightweight who wouldn’t last, a semiliterate tribesman who could barely deliver a speech. The C.I.A. station chief was laying bets that Saleh would be out by the spring of 1979.”

But Mr. Saleh reached out to veteran Yemeni politicians for advice and support and recruited a new class of technocrats, Professor Burrowes said. “For whatever psychological reason, he didn’t feel threatened by them,” he said.

By most accounts, Mr. Saleh was not devoutly religious, but he paid attention to managing the Islamists who thrived in Yemen’s religious culture. When Yemeni men who had fought against the Soviet Army in Afghanistan returned home in the 1990s, he saw that they were integrated into the security forces. Only when Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula began to attack his regime did he step up combat against the group.

Mr. Saleh promoted fellow Sanhan tribesmen serving in the army and security forces, among them his son Ahmed Ali Saleh, who was in charge of the elite Republican Guards, and a nephew, Yahya Saleh, who worked closely with the United States on counterterrorism.

On Saturday, he spoke publicly about changing allegiances one more time, abandoning the Houthis and reaching out to Saudi Arabia and other regional powers who had fought against them for three years with a devastating bombing campaign.

“We will turn a new page by virtue of our neighborliness,” Mr. Saleh said in a televised speech. But his long story, which had weathered so many crises, had run out of pages.