By Farea Al-Muslimi and Sarah Knuckey

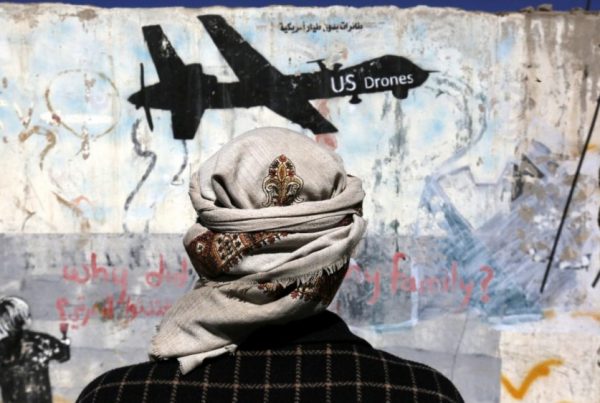

While we were visiting Yemen this month, the United States conducted a drone strike against alleged al-Qaeda members in Mareb Governorate, reportedly killing two suspects while they were traveling in a vehicle. As one of over 116 drone strikes in Yemen this year, the attack made little news. But the circumstances of this strike, combined with information shared with us by the governor of Mareb, a key U.S. ally, raise very serious questions about whether the U.S. is following its own drone strike rules, or, perhaps, whether those rules are actually in force.

U.S. policy and rules purport preference for capture of suspects

For years, the U.S. government has told the American public and the international community that it only uses lethal force outside areas of active hostilities where conditions laid out in the Presidential Policy Guidance (PPG) (2013) are fulfilled. The PPG was announced to much fanfare in May 2013 by President Barack Obama, and it has been heralded by supporters as setting out strict rules for when lethal force can be used. Indeed, a major national security speech by Obama, and the publication of a summary of the rules in 2013, led to reduced criticism of U.S. lethal force operations in the following months.

The PPG emphasized a preference for capturing, rather than killing, suspects. The first page of the PPG included this key statement:

Capture operations offer the best opportunity for meaningful intelligence gain from counterterrorism (CT) operations and the mitigation and disruption of terrorist threats. Consequently, the United States prioritizes, as a matter of policy, the capture of terrorist suspects as a preferred option over lethal action and will therefore require a feasibility assessment of capture options as a component of any proposal for lethal action.

The PPG then set out that the before any operation could proceed, the following must be satisfied:

(i) an assessment that capture is not feasible at the time of the operation;

(ii) an assessment that the relevant governmental authorities in the country where action is contemplated cannot or will not effectively address the threat to U.S. persons; and

(iii) an assessment that no other reasonable alternatives to lethal action exist to effectively address the threat to U.S. persons.

The rules have been key to U.S. government efforts to legitimize their lethal force: U.S. officials have often relied on these rules in responding to critiques about U.S. counterterrorism actions and allegations of civilian casualties and counterproductive operations.

Two developments under the Trump administration have cast doubt on where and how the PPG now applies to U.S. operations.

In March 2017, reports indicated that the Trump administration had granted Defense Department requests to deem areas of Yemen and Somalia as “areas of active hostilities” and thereby relax or exempt operations in such areas from the constraints imposed by the PPG.

In September, The New York Times’ Charlie Savage and Eric Schmitt reported that the Trump administration was “preparing to dismantle key Obama-era limits on drone strikes and commando raids outside conventional battlefields.” The article discussed a number of concerning proposed changes, but did not mention any changes to the capture feasibility rules. The NYT subsequently reported that the changes went through, although the administration has not released the new rules.

However, we have seen no reports that the rule requiring no feasibility of capture has been rescinded or loosened in the context of U.S. operations in Yemen.

Yemeni official puts capture preference into question

Earlier this month, we spent several hours meeting with Mareb Governor Sultan Bin Ali Al-Aradah. We discussed at length his views about counterterrorism and armed conflict in Yemen. As a local tribal leader and governor of the provincial stronghold of Hadi-led Yemeni government forces, Al-Aradah is a powerful and influential politician—and one of the most powerful Yemeni government officials in the country. A critical partner of the Saudi-led coalition and fierce opponent of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), he is also an important local U.S. ally.

The governor told us that the Nov. 2 drone strike took place in an area that his security forces could access. More generally, the governor lamented the United States’ failure to inform local officials, or to provide information that could lead or facilitate the capture of suspected members and leaders of AQAP. “As long as we’re able to do the job ourselves, inform us….if we can, we want to arrest,” he stated.

The governor is not a drone strike opponent. He stated that “sometimes drones work,” but he had real concerns about how the U.S. deploys its force in Yemen. He explained why he has voiced a strong preference for capturing al-Qaeda suspects, a preference which he stated he has shared with the U.S. ambassador to Yemen in the past. The governor explained that capture enabled questioning of suspects and created the potential for gaining critical information about armed group activity. He added that the unilateral nature of U.S. counterterrorism concerns him, and makes fighting AQAP harder for his government and security forces: “Protect civilian lives, and the psychology of those in the city, and most important, we don’t want to pass people to the sympathies of the terrorists…” He expressed concern about the U.S. relying on poor (mis)information, which led to mistakes in strikes and civilian harm, and the risk of creating more terrorists. The governor also argued that arresting suspects, often by working through tribal relations and customs, would help strengthen the rule of law, and expressed concerns about the legality of and accountability for U.S. drone strikes.

“We want the state to stand on its feet and to take every criminal to court—and at the very least countries that use drones to come up with legal accountability for their use,” Al-Aradah told us. “That’s why I always say the flow of info and actions needs to come through local security agencies. Right now, there is no one to hold accountable.”

During our conversation, the governor was flanked by his chief of security, chief of intelligence, and chief of special forces, all of whom expressed strong agreement with his points.

The governor’s criticism was also echoed by tribal sheikhs we met in Mareb.

“The problem is that America takes the exclusive role on counter-terrorism,” criticized tribal leader and member of parliament, Sheikh Ali abdu Rabu al-Qadhi.

Sheikh al-Qadhi added that such strikes, especially when they kill innocent civilians and individuals from prominent local families, can lead to AQAP expanding, and communities taking out grievances on tribal leaders and the local government. Sheikh al-Qadhi also criticized the legality of drone strikes: “When a country like America chooses to assassinate outside the law, this is a big problem.”

Other tribal leaders also expressed disappointment and frustration at the United States’ lack of information sharing and cooperation with local authorities and tribes who are on the front lines against AQAP—fighting to prevent recruitment and influence in their communities.

“It’s not just about the drone,” as another Sheikh put it. “This conflict is local and when there’s a strike the whole village can join the fight. We believe that it should be our local communities that should fight al-Qaeda.”

The leaders also criticized the overly military focus of U.S. counter-terrorism approaches, recommending that far more support is needed for development programs, education, and partnerships.

Questions for the Trump administration

The governor’s claim that security forces could have accessed the area in which the strike took place raises many questions about the U.S. decision to take the strike.

The Obama administration’s PPG was meant to bring some level of constraint and accountability to U.S. counter-terrorism operations. In light of the Trump administration’s murky attempts to roll back these rules, the governor’s account raises crucial questions that merit immediate answers:

- Does the capture preference of the PPG continue to apply after Trump administration revisions?

- Did the U.S. conduct a capture feasibility assessment for the Nov. 2 strike? Did the U.S. government conclude that the governor and his security forces “cannot or will not” address the threat? If so, based on what information and engagement with local authorities? Why was it not a “reasonable alternative” to conduct an operation to capture the suspects?

- Beyond Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, where exactly has the Trump administration declared “areas of active hostilities”?

The Nov. 2 drone strike is not an entirely unique case, and several past U.S. drone strikes in Yemen have also raised serious concerns that attacks were conducted when capture was feasible. The situation in Mareb, however, does seem to be a particularly concerning case.

Mareb is perhaps the most stable governorate in Yemen, with an extensive presence of Yemeni military forces and U.S.-allied Saudi and Emirati advisers and special forces on the ground. At its head is a powerful governor, with deep trust amongst tribal leaders, and eager for more engagement, support from, and security cooperation with U.S. authorities. Yet Governor Al Aradah’s account indicates that coordination and information sharing with local allies is minimal. Understandably, he’d like to know why.